This week on February 12 we celebrated the birthday of our 16th President, Abraham Lincoln. There are a few reasons Lincoln is a favorite of mine beyond his historic accomplishments. He was the first U.S. President to be embalmed, a story I shared in another post.

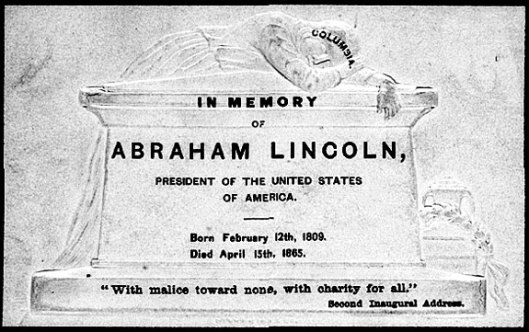

This is a mourning card printed soon after Lincoln’s death. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Books and Special Collections Division.

But Lincoln’s also the only President whose funeral became a 14-day, multi-state affair that covered over 1,600 miles, went through more than 160 communities, and involved about 30 million mourners. This year marks its 150th Anniversary and efforts are in the works to re-create the trip, despite the fact funds have been somewhat lacking to finance it.

Today in Part I, I’ll cover the first half of Lincoln’s funeral procession through Maryland, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York.

Although John Wilkes Booth shot Lincoln at Ford’s Theater on April 15, 1865, the assassin originally wanted to do it on March 15 (the Ides of March) to emphasize his view of Lincoln as a tyrant. This illustration appeared in Harper’s Weekly magazine.

Funeral at the White House and Rotunda Viewing

After four days of preparation, Lincoln’s White House funeral was held on April 19 in the East Room with about 600 in attendance. From the time the body had been made ready for burial until the last services in the house, it was watched by a guard of honor, the members of which were one major general, one brigadier general, two field officers, and four line officers of the Army and four of the Navy.

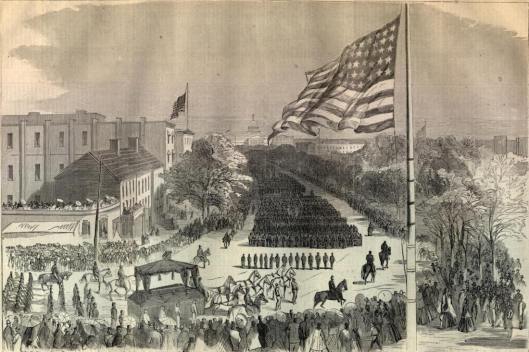

The procession from the White House to the Capitol Rotunda covered about three miles and took over two hours. The Twenty-Second United States Colored Infantry (organized in Pennsylvania) landed from Petersburg and belatedly marched up to a position on the avenue, played a dirge and headed the procession to the Capitol.

Over 100,000 people lined the streets. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper reported: “Every window, housetop, balcony and every inch of the sidewalks on either side was densely crowded with a mournful throng to pay homage to departed worth. Despite the enormous crowd the silence was profound. It seemed akin to the death it commemorated.”

Ben Perley Poore, wrote: “At 2 p.m., the funeral procession started, all of the bells in the city tolling, and minute guns firing from all the forts. Pennsylvania Avenue, from the Treasury to the Capitol, was entirely clear from curb to curb. Preceding the hearse was the military escort, over one mile long, the arms of each officer and man being draped with black.” Illustration from Harper’s Weekly.

The next day, about 40,000 mourners passed by Lincoln’s open casket in the Capitol Rotunda. Union officer William Gamble supervised the honor guard and described the scene, including an elderly mourner who bent the rules a bit:

While I was standing at the head of the coffin preventing people from touching it, one old lady over 60 years old watched me closely, and quick as thought darted down her head and kissed the President in spite of me. I could not find it in my heart to say a word to her, but let her pass on as if I did not see it. You can form no idea of the scenes I saw.

The catafalque (a raised structure on which the body of a deceased person lies) that supported Lincoln’s casket in the Capitol Rotunda continues to be used for all who have lain in state there. Most recently, it was used in 2013 after the death of U.S. Senator Frank Lautenberg, whose body lie in repose in the Senate chamber after his funeral in Secaucus, N.J.

This map shows the seven states and major cities the Lincoln funeral procession went through. A total of 13 different funerals were held, with one impromptu one in Michigan City, Ind.

Lincoln’s funeral procession, with a few deletions, traces the same route he took from Springfield, Ill. to the White House in 1861 when he became President. Over the course of that journey, Lincoln’s casket would be removed from the train several times for public memorial services and viewings. As you can imagine, embalming was a must in order to forestall decomposition.

Lincoln’s funeral car was not constructed just for the occasion. In early 1865, the United States Military Railroad delivered the 1865 equivalent of Air Force One to President Lincoln, a private railroad car. Yet Lincoln never used the railroad car, named The United States, while he was alive. After his death, it was modified to serve as his funeral train and called “The Lincoln Special.”

Postcard of the funeral train “The Lincoln Special” that carried him across seven states and through over 160 communities. A portrait of Lincoln was placed above the cowcatcher on the front of the engine.

Also on board were the disinterred remains of Lincoln’s son, Willie, who died at the age of 11 in 1862 at the White House. Per the family’s wishes, he would be buried with his father in Springfield, Ill. Lincoln’s wife remained in mourning at the White House, but son Robert Lincoln rode the train as far as Baltimore before returning to Washington.

Baltimore, Md. and Harrisburg, Pa.

Lincoln’s funeral train traveled first to Baltimore on April 21. His coffin was borne to the Merchant’s Exchange Building and opened for public view for only about an hour and a half. The train then departed for Harrisburg, Pa., a 58-mile trip. The coffin was then carried by hearse to the state House of Representatives, placed in a catafalque, and opened for public viewing.

Philadelphia, Pa.

The train departed Harrisburg for the 106-mile journey to Philadelphia where it arrived at the Broad Street Station. A hearse took Lincoln’s coffin through Philadelphia’s streets teeming with mourners to Independence Hall. There the coffin was placed in the East Wing where the Declaration of Independence had been signed. Viewing that evening was by invitation only.

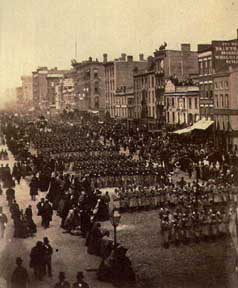

Philadelphians were eager to catch a glimpse of Lincoln’s funeral hearse. Thousands flocked to Independence Square in hopes of viewing him up close. As the photo shows, spectators even climbed on rooftops to get a look.

On the morning of April 23, long lines started forming. At its greatest, the double line was three miles long and wound from the Delaware River to the Schuylkill River. An estimated 300,000 people passed by Lincoln’s open coffin and the wait was up to five hours. The crowds were so immense that police had trouble maintaining order. Some people had their clothing ripped, others fainted and one reportedly broke her arm.

Despite Thomas Holmes’ thorough embalming, Lincoln’s body did suffer a little from the repeated exposure. According to Bradley R. Hoch, “As soon as the entrances closed and the public was out of the Assembly Room…embalmer Brown cleaned Lincoln’s face of the dust that had accumulated during 33 hours in Philadelphia.”

New York City, N.Y.

On April 24, Lincoln’s funeral train left Philadelphia headed for New York, an 86-mile trip. While in New Jersey, the train arrived at the Jersey City station and Lincoln’s coffin was taken by ferry across the Hudson River. It was then borne to City Hall where it was carried up the circular staircase under the rotunda. After the coffin was placed in a black velvet dais, the public was admitted. At one point, it was reported that more than 500,000 people waited in line to view the President.

David T. Valentine wrote: “A ceaseless throng of visitors were admitted to view the body, while many thousands were turned away unable to obtain admittance. All classes of our citizens, the old and the young, the rich and the poor, without distinction of color or sex, mingled in the silent procession that passed reverently before the bier.”

An account from the New York Times mentioned Lincoln’s appearance: “It will not be possible, despite the effection of the embalming, to continue much longer the exhibition, as the constant shaking of the body aided by the exposure to the air, and the increasing of dust, has already undone much of the…workmanship, and it is doubtful if it will be decreed wise to tempt dissolution much further.”

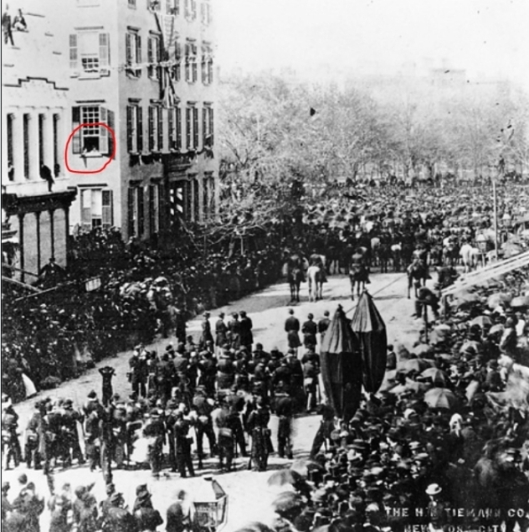

The procession of Lincoln’s hearse from City Hall to the train station was a grand affair. An estimated 75,000 marched in the huge procession through New York’s streets. Windows along the route are said to have rented for up to $100 a person. When the procession neared Union Square, it passed Theodore Roosevelt’s grandfather’s home where the six-year-old future president was viewing the procession from a second-story window.

The red circle indicates where young Theodore Roosevelt, the future 26th President, observed Lincoln’s funeral procession to the Hudson River Depot.

Albany and Buffalo

On April 26, the next stop on Lincoln’s funeral procession was New York’s capitol, Albany. Planned to be simpler than the others but no less respectful, the procession included only three companies of National Guardsmen, three companies of firemen bearing torches, state officials, members of the Legislature, and city authorities. When the hearse arrived at the Capitol, the remains were taken to the Assembly Room.

W. Emerson Reck wrote: “As many as 70 viewers a minute (total nearing 50,000) passed by the coffin between 1:30 a.m. and 2 p.m. A mass of human beings, estimated at 60,000, crowded along the streets for more than a mile when the procession escorting the remains from the Capitol to the New York Central station.”

Arriving in Buffalo on April 27, Lincoln’s coffin was transported to St. James Hall in a hearse drawn by six white horses dressed in black. About 100,000 people passed by the coffin during the day.

John Harrison Mills, a veteran whose leg was shattered at Second Bull Run, guarded Lincoln’s coffin in St. James Hall in Buffalo. “I cannot remember how it came to pass that I was chosen to stand guard at the head of our beloved President Lincoln on that momentous day,” he said. Photo courtesy of Benedict R. Maryniak.

Mourners included the 13th U.S. President Millard Fillmore and future President Grover Cleveland. There was no formal funeral procession in Buffalo since they had staged a complete mock funeral on April 19 not knowing then it would be a stop on the train’s itinerary.

Despite his criticism of Lincoln’s war policies, Millard Fillmore was on hand to pay tribute to him upon his arrival by train at Buffalo.

Next week in Part II, I’ll tackle the rest of Lincoln’s journey back home to Springfield, Ill. and his final interment there.

I love anything Lincoln! Great post. Cannot wait until Part 2.

Quite an interesting article Traci..I’m looking forward to part 2!

Did J.M. Whittemore ever do a mouning card sold to commrnerate two week long funeral for him ?

Hi, Noah! I don’t know if he didn’t but it’s possible.